“Wow! Grammar! Something that I haven’t heard about for a long, long time.”

I can imagine that playing through your head time and time again as you show up for your First Language English class, probably you would continue for weeks on end. Before you know it, and contrary to popular belief, you’ll be at the end, and you’ll have never touched a lick of grammar.

What a weird thing to happen given just how important grammar is – but you certainly won’t need to understand grammar formally in the 0500 curriculum, although you’ll definitely be expected to know how to use it correctly.

As you probably know, grammar refers to the rules that guide what is correct usage of the English language.

Your tenses, past, present, and future. Your keeping consistency, your using the rules at the right time in the right place to convey exactly the kind of meaning that you want. It is like the air we breathe – necessary for a smooth daily existence, forgotten when it’s there, but when it’s gone, everybody notices as they swim from the deep waters to the itch separating them from the air to breathe it all in.

And so it is with grammar—so important, yet so easily forgotten.

Unfortunately, if you are hoping to learn about grammar in the course of your daily first language English life, bad luck because you’re not going to. After all, in first language English, people pretty much assume that you just know everything. You’re a first language speaker, unfortunately. In many cases, though, that’s an assumption that’s not actually true unless you’re telling me that you know every single grammatical rule out there.

The good news is twofold:

Firstly, you don’t need to memorize every single grammatical rule in order to function, and in fact, most speakers or users of the language don’t.

What’s a lot more natural is that we just make use of the language the way experience teaches us.

The second thing is that there’s no real test of grammar—at least, in an explicit sense— with grammar drills or anything like that. The bad news is if you’re not one of those people who has that sort of explicit knowledge, then chances are you’re just going to pass through the entire course not learning clearly or intuitively about those rules; Thrown into the deep end, it’s your job just to function and level up. You have no idea how many people go through this.

People who are taking first language English, when really given their foundational skills, they should actually be doing second language. Never actually speaking English at home, only here to take it up because they need it for university.

Well, nowhere is the situation as dark or sad as you might imagine, because you’d be surprised what human beings can learn when under pressure.

But trust me, I’ve seen so many people just come and go, passing by, never really learning the rules, even though they would have made life so much easier for them.

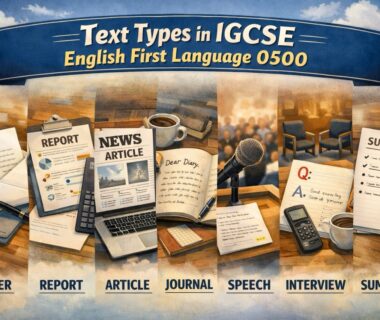

That’s why right here we have The Complete Grammar Guide For IGCSE English, a small refresher for you to learn grammar in case you want to refresh your understanding of the foundational rules and how all of them work together with one another.

Real talk though – it’s probably going to be hard to pick up grammatical rules all along. In any case, that isn’t what first language English is about: This class is after all more about appreciating the different ways to use language, the different kinds of meanings that are produced.

You can approach to some extent without memorizing grammatical rules, although to some extent, of course, the rules themselves are what define meaning, so there is a challenge then in understanding enough grammar and appreciating language well enough that somehow or another your understanding of the rules informs your ability to create, understand, and appreciate meaning.

While at the same time you don’t get too caught up with memorizing things. It’s up to you to discover that balance.

If you pick up the complete IGCSE grammar guide, I hope you’ll think of this as you reflect along the way. Thank you for your support, and look forward to seeing you in the next ones!