If you are reading this, you’ve probably started the journey of exploring English proficiency examinations.

In particular, you might be thinking about the IGCSE English exams (or have taken them) already, and you may now be considering taking the International English Language Testing System (IELTS) or a comparable English proficiency exam such as the TOEFL. These exams, widely recognized and respected, can open doors to further education and career opportunities.

That said, they serve different purposes and target different skills, and parents are often a little confused about the differences between them.

No worries, though – that’s why this post exists; in it, you’ll discover some of the differences between the IGCSE English exams and also the IELTS exam, and I hope that it will give you the understanding that you seek 🙂

Let’s dive in!

Firstly, let’s briefly introduce both exams.

First, let’s talk about the IGCSE English exams.

The IGCSE is an internationally recognized secondary school qualification, and it provides two primary English language (proficiency) exams – First Language English (0500), and English as a Second Language (0510).

First Language English is primarily designed for students who have English as their first language. It focuses on developing students’ ability to communicate clearly, accurately, and effectively in both speech and writing. Students are encouraged to use English in a variety of contexts and to a high level of sophistication, with a rich vocabulary and complex sentence structures. English as a Second Language, on the other hand, is designed to teach English to students who haven’t had extensive exposure to English in their prior schooling or home environments.

On the other hand, the IELTS examination is an international standardized test of English language proficiency for non-native English language speakers.

The IELTS exam comes in two versions: IELTS Academic, for those who want to study at a tertiary level in an English-speaking country, and IELTS General Training, for those who want to work or undertake training in an English-speaking country.

Let’s now talk about structure.

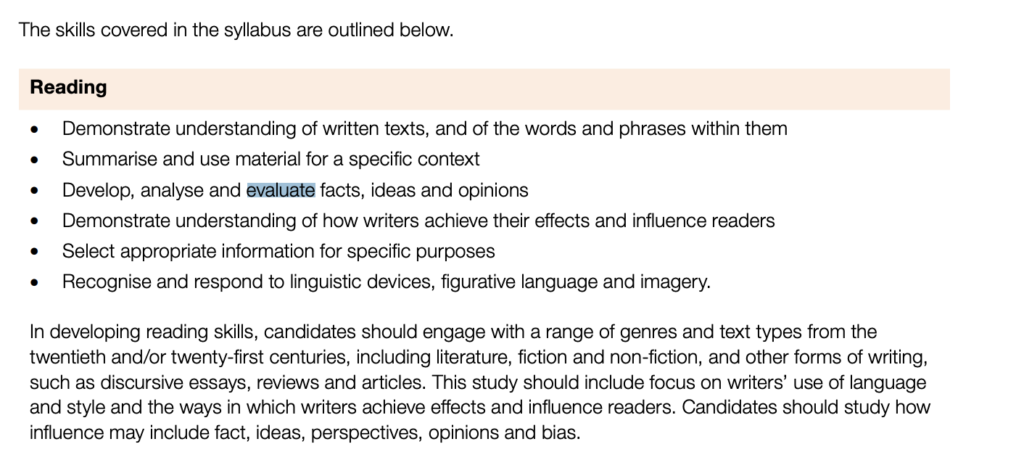

First language English requires students to complete assessments in reading and writing, and it asks them to complete exam papers that require them to analyze and deal with texts on a level that requires an appreciation for language and how to analyse and comprehend it.

Generally, the First Language English paper is broken down into two exam papers, one dedicated to reading comprehension and various other questions that come with it, and another paper dedicated to directed writing and narrative/descriptive writing; some students also do coursework, which also involves creating writing samples dedicated to creating higher order narrative or descriptive writing except without as much of a time constraint as what they would encounter with Paper 2.

IELTS, however, is broken down into four different subsections, each of which has their own exam – reading, writing, listening, and speaking. Additionally, there are two variants of the exam – the IELTS Academic for students who want to study in foreign countries as part of a student visa requirement or a conditional offer, and the IELTS General paper, for people who want to work overseas to fulfill their work visa requirements.

Let’s now talk about purpose.

The IGCSE English exams are assessments that demonstrate evidence of academic pursuit of the English language in a schooling environment with the aim of obtaining a secondary school qualification. They are assessments that allow teachers to develop teaching examples and experiences to allow their students to explore and understand the English language in different ways depending on the level that the subject is being taken at.

IELTS, however, is an internationally recognised English examination that is required both for entry to university is as well as to certain countries, forming part of the Visa requirement for students who want to work overseas (hence why you see that some students insist on getting writing scores for the IELTS that are above 6.5 – it is part of their visa requirement).

But do you need to take it though?

In this blog post, we will delve into the specifics of both the IGCSE First Language English and the IELTS examination, breaking down their structure, purpose, content, and the skills they aim to develop. We’ll also discuss their relevance and implications for you, helping you decide which one fits best with your future plans.

Let’s start talking about who needs to take the IELTS.

Generally speaking, you will need to take the IELTS if you are a resident of a non-English speaking country and you are seeking either employment or formal education within an English speaking country.

But Victor, you might say – I already took the first language English examinations!

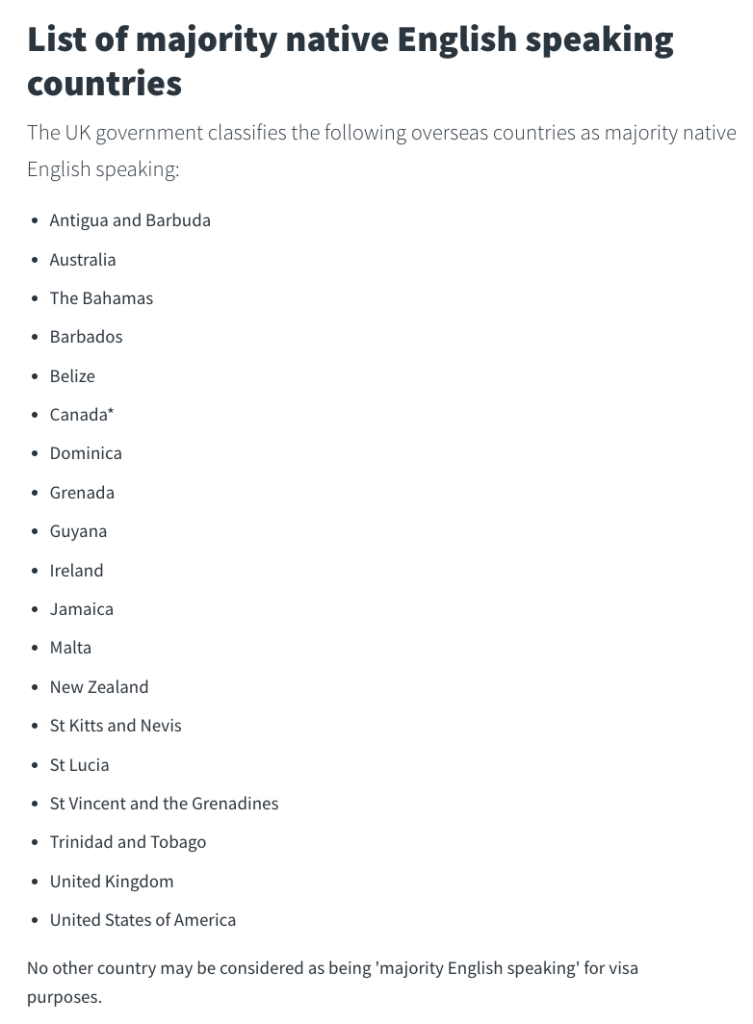

Do I really need to take the IELTS? Unfortunately, the answer to this question is most likely a yes – many countries and jurisdictions do discriminate on the basis of where you originate from geographically (example: The UK Home Office designation of majority English speaking countries), which does mean that even if your English is significantly better than someone from an English speaking country, you will still have to take the IELTS in order to prove your capabilities.

In other words, if you are not from one of these countries…

…It’s likely that you’ll have to take the IELTS.

See:

The most dramatic illustration that I have seen of this is the case study of my friend Alicia’s conditional offer to enter Cambridge University to study law – Although she had taken FLE and even A Level English Literature, because she was from Malaysia, she was required to take the IELTS and to receive a score of 8.5 and above (essentially the same overall score as me – but it was a requirement!) in order to meet the terms of her conditional offer despite the fact that Cambridge specifies that it requires a minimum overall band of 7.5, clearly demonstrating that first of all your mileage will vary, and second of all that you may need IELTS even if you obtain A*’s in First Language English or otherwise.

…Unless you receive an exemption.

Another natural question arises:

Can you use an IGCSE English qualification or any national curriculum English exam in lieu of the IELTS?

It’s true that the IELTS is not cheap (MYR858 to register, the last time I checked), but as a resident of a non-English speaking country, In most cases, you should expect to take both the IGCSE English qualification that you have chosen to take (or SPM English/whatever your national English curriculum reflects) alongside the IELTS.

That said, it is possible to take First Language English rather than take the IELTS exam in order to enter a university (sometimes)… But note that such a scenario is the minority of all cases and would typically constitute a situation of a waiver of IELTS or comparable English proficiency exam rather than anything else.

This may be something that you should consider doing a little more if budget is a huge concern for you and taking one extra exam is likely to break the bank… But it is important to note that not all universities will accept the secondary school qualifications that you’ve chosen, and you would probably cover more ground if you were to take IELTS as well and therefore have more options at the end of the day.

It is possible for you to identify a list of universities that only require a sufficiently strong FLE grade, but personally I think that that’s a waste of time – as long as your mastery of the English language (which is the most important thing in the first place) is secure, you’ll have no problem taking the IELTS and obtaining a good grade, and the IELTS will serve as the exam that validates your English proficiency.

The natural next question is…

Can you simply take the IELTS rather than even take a secondary school qualification in the first place?

While I think that the answer to this question is a yes, particularly if the student is able to obtain a high score in the IELTS despite not having a secondary school qualification in English, success at IELTS requires a student to have a decent grasp and formative understanding of the English language, the development of which requires numerous years of experience and also exposure to good teachers.

A student who has received adequate preparation for this throughout the course of their secondary school career, which would naturally lead into the obtainment of a secondary school qualification such as the IGCSE or otherwise, would be much more likely to obtain a good IELTS score; correspondingly, while it is possible to develop the requisite mastery of English to do well in the IELTS without necessarily taking First Language English or English as a Second Language, it would be rare or otherwise unlikely for us to find a student who is able to do well at the IELTS who has not done any sort of secondary school English qualification, because that would mean that they had not learned in a structured learning environment.

It is not something that I recommend – getting formal training from a skilled instructor is important.

That said, those of you who are considering IELTS and IGCSE English may be wondering…

Which exam is more difficult?

It depends on what you’re comparing exactly.

I think that many people would say that First Language English is more difficult compared to the IELTS, because the first language English examination is an examination of analysis and critical thinking as well as writing that requires not only comprehension and basic sentence construction, but recruits much more sophisticated skills that require a student to develop a strong understanding and facility with language usage.

On the other hand, IELTS is an exam that aims to assess how well students can perform in everyday English language usage situations; accordingly, it requires students to demonstrate mastery of the English language across more modalities, although it does not require advanced language skills in order to do well in it.

IELTS merely requires the ability to speak, write, and think fluently and articulate one’s thoughts, demonstrating good comprehension along the way, and in that sense is more similar to English as a Second Language rather than to First Language English because of its focus on the mechanics of the English language rather than on using it for more cognitively demanding tasks such as analysis and evaluation, per the First Language English syllabus.

It’s crucial to note, though, that just because First Language English is of a high(er) level of difficulty relative to the IELTS, that does not mean that a student who is able to do well at FLE will automatically be able to do well at the IELTS – Because First Language English students do not need to practice listening or speaking, it’s still quite possible for a good FLE student to be caught off guard by the IELTS exam and therefore crucial to obtain specific practice for it.

Are there some other considerations that I should be aware of?

IELTS results are only valid for two years, while IGCSE results are valid for life.

This means that you generally have no reason to take the IELTS extremely early – most students who take IELTS for academic purposes do so either right after they obtain their conditional offers from university, or sometime during the year that they are taking A Levels, IB, or whatever pre-university qualification it is that they are working on.

At the same time, while there isn’t an immediate rush for you to do the IELTS, it is something that you’ll want to make sure that your child can do well on. With that in mind, you may be asking yourself…

“Can my child do well for FLE and for IELTS?“

At the end of the day, the most important factor that underpins whether a student will succeed in the First Language English or IELTS exams is their raw ability at using the language effectively – the extent of their grammaticality, the strength of their skills of analysis, their ability to comprehend written information, and otherwise; it is something that requires specific practice and training for, and it isn’t something that you’ll automatically be good at just because you’ve spent a certain number of years in school.

Still, at the end of the day, although a student’s abilities and practice for one of these exams is likely going to correlate with their performance in the other, it’s crucial to perform targeted practice for each exam because their curricula are markedly different and they assess different things.

It’s crucial to develop a strategy of targeted practice for any exam, and the same is true whether you’re taking First Language English or IELTS, and it is important to be able to get a sense of the difficulty and your preparedness for the curricula through an independent perspective.

Consider dropping a message if you’d like to assess your child’s suitedness for the curricula, and I’ll look forward to chatting with you soon!